By Jessica Scott-Reid

Jessica is a Canadian writer, animal advocate and plant-based food expert. Her work appears regularly in media across Canada and the US.

Hundreds of wildfires burning from coast to coast in Canada are sharpening the focus of discussions about the causes of climate change and how to mitigate it. The oil and gas sector has typically taken most of the heat, along with transportation and manufacturing, as mainstream media regularly report on the harms caused by these industries. Yet, despite animal agriculture’s significant contribution to the climate crisis, coverage of this has been glaringly absent. Case in point, many stories on the Canadian wildfires are making the link between these disasters and climate change yet barely a mention of the role of animal agriculture.

Photo: Garrett Butler on Unsplash

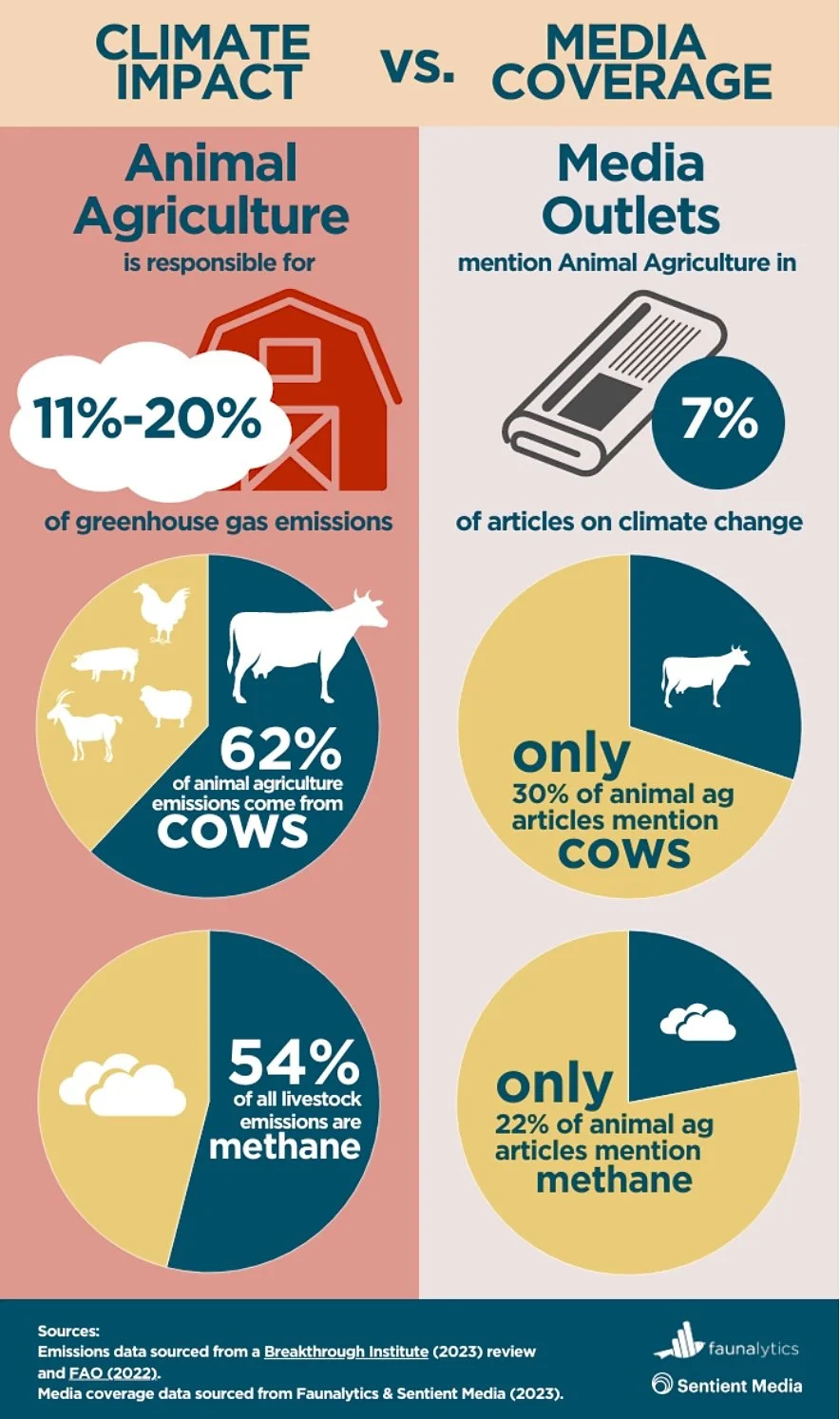

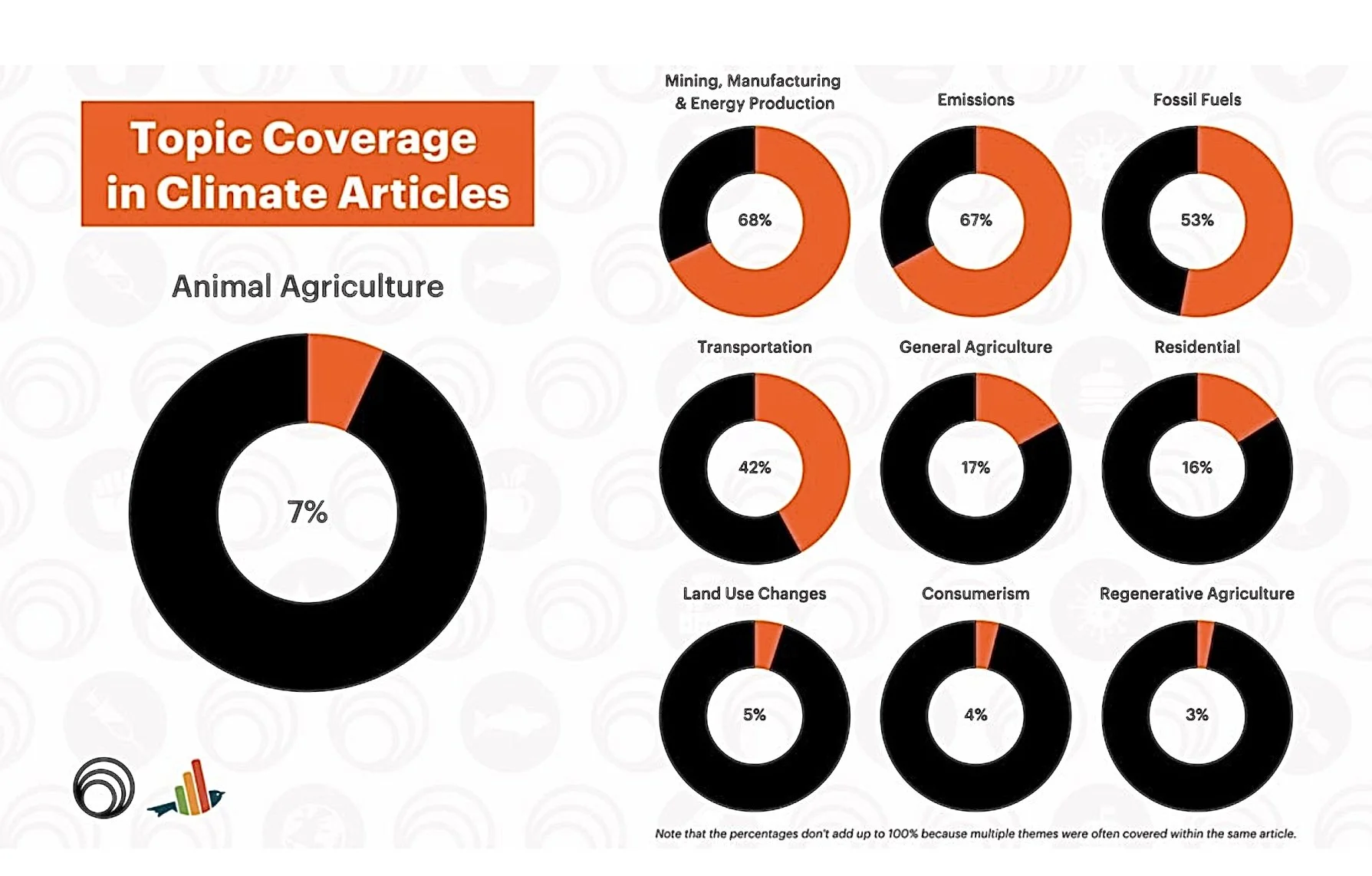

About six years ago the saying emerged, “The elephant in the room is really a cow,” calling attention to a widely ignored truth: that animal farming occupies a major slice of the climate chaos pie chart, but few want to talk about it. Now, we have evidence to support this. New research from Faunalytics and Sentient Media has found that only 7% of US media coverage of climate change focuses on animal agriculture. This is a shockingly low number given the sector is a leading contributor to human-caused greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, water pollution and land use.

One of the key findings of the research, which examined 1,000 articles from major US media outlets, found that “only a handful of stories reported in depth on the connection between consuming animal products and climate change.” The articles that did mention animal agriculture, “failed to discuss the emissions and environmental degradation caused by the industry, let alone the importance of reducing meat consumption or switching to a plant-based diet to fight climate change.” And when diets were mentioned, “the effectiveness of plant-based diets was sometimes downplayed or, more often than not, presented almost as an afterthought rather than a legitimate strategy to mitigate climate change.” Further, the research found that the “animal agriculture industry is often portrayed as a victim of climate change rather than a significant cause.”

Source: “Animal Agriculture Is The Missing Piece in Climate Change Media Coverage“ report by Faunalytics and Sentient Media

In a follow up panel discussion on the research, “Making the climate connection,” hosted by Sentient Media and Faunalytics, reporters, editors, scientists and other climate communicators weighed in on why media may be ignoring the cow in the room. Washington Post food columnist Tamar Haspel put it bluntly: “There are a number of reasons, but the predominant one is that people like meat, so writing about it becomes kind of a challenging thing. Because you basically end up telling people to eat less beef and that’s a message people tend to be hostile to.”

Haspel says writing about meat as a climate change contributor is different from writing about issues such as fossil fuels, because when it comes to the latter, “there are alternatives. But when we talk about meat, the alternatives are unpalatable to a lot of people, literally [e.g., beans, lentils, plant-based meat alternatives] and figuratively [e.g., reducing meat consumption].” As a result, audience demand for such coverage and content is perceived to be low which inevitably influences story selection.

Consumer demand for plant-based alternative proteins is growing again after a dip in sales after an initial surge during the Covid pandemic. Photo: A pizza with a Beyond Meat plant-based topping served in Canada by restaurant chain Pizza Hut

A similar situation was observed during the COVID-19 pandemic, when media coverage regarding the well-established connection between factory farming and zoonotic disease risk was notably lacking. At the time, Dr. Hank Rothgerber, professor of social psychology at Bellarmine University in Kentucky, researching human-animal interactions in the context of food choices, told Sentient Media that there is much psychology at play in these circumstances. “People are attached to their behaviors, to their habits,” he says. “Meat-eaters have a meat-motivated mind. Those folks who are most attached to meat, they don’t welcome this information. They will go to great lengths to distort it, to convince themselves that it’s not true.”

Crowded factory farms full of stressed, genetically identical animals have been shown to be perfect mixing vessels for viral mutations that can lead to future pandemics. Photo: Jo-Anne McArthur, We Animals Media

A strategy to rationalize meat-eating during a pandemic likely caused by a zoonotic disease, Rothgerber explains, and which can also be applied to climate change, is to “other” the problem. Making the issue far-removed can allow individuals to feel less compelled to do something about it. For example, he says, “there is much more appetite for attributing [the pandemic] to a wet market in China. That’s more palatable to American meat-eaters.”

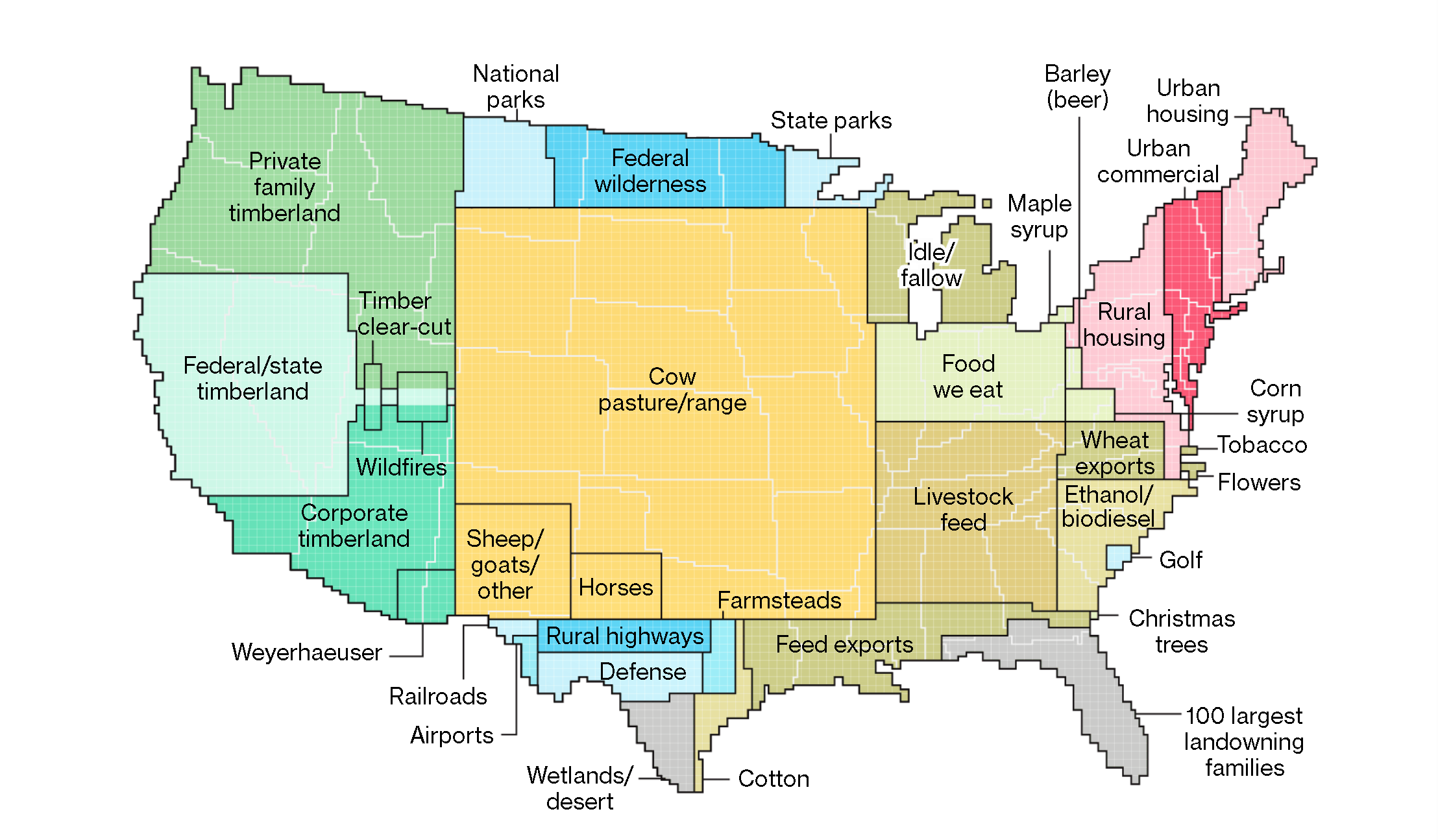

Similarly, well-known author and journalist Michael Grunwald, said during the panel, that “most of what we are talking about [regarding animal agriculture and climate change] is farms and forests,” which he calls “fly-over country, we fly over it or we hike through it,” it’s not really in our own backyard. “So we get the fruits of it, but we don’t really think about it in our day-to-day life, and I don’t think people are all that interested in it.”

Alternatively, Sonalie Figueiras, founder and editor-in-chief of award-winning impact media platform Green Queen Media, told the panel that food simply hasn’t had its climate media moment yet. She pointed to the rapid uptick in media coverage of other sectors in recent years, believing the same can still come for food production once audiences are better informed. Today, she says, “that context is just not there yet for most people, that we aren’t sorting out the climate crisis without sorting out our food.”

Real chicken, grown from animal cells, produced by cultivated meat pioneer Upside Foods

Media is heavily relied upon to bridge that gap between science and the public, to advise us so we can make informed decisions. So, what can be done to move the media to report on the connection between animal agriculture and climate change? Panelist Matthew Hayek, environmental researcher and assistant professor at New York University, pointed out a general need for journalists to become more climate literate. This includes gaining a fundamental understanding that "the climate problem is coming from under the ground, that is fossil fuels, and also the surface of the earth, that is all the land use change and farming.”

Animal farming, a combination of pasture and cropland for animal feed, takes up 41% or 781 million acres of the contiguous United States. By contrast, food that people, not animals, eat takes up 77 million acres. For comparison, urban areas occupy 70 million acres. Source: USDA, Bloomberg

Journalists have a responsibility to provide accurate and full picture coverage, and the public has the right to know the whole story. Covering Climate Now (CCN)—the world’s largest media collaboration (of which PFN is a partner), helping newsrooms “tell the whole climate story”, suggests that when it comes to “reporting on extreme weather, it’s essential to explain the climate connection so audiences understand how the warming planet is changing their lives.” This needs to include the impacts of animal agriculture. As CCN notes, “An extreme weather story that doesn’t mention climate change is incomplete and potentially even inaccurate.” Similarly, a climate story that doesn’t mention animal agriculture, is equally incomplete.

SIGN UP BELOW FOR OUR MONTHLY EMAIL WITH LINKS TO OUR LATEST BLOGS AND A REMINDER TO FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA FOR WAYS TO HAVE A POSITIVE IMPACT ON LIFE ON OUR PLANET.