Opinion: NGOZI OKONJO-IWEALA

This story originally appeared in https://www.newsweek.com It is republished here as part of Planet Friendly News’ partnership with Covering Climate Now, a global collaboration of more than 250 news outlets to strengthen coverage of the climate story.

World leaders have a formidable task: setting a course to save our future. The extreme weather made more frequent and severe by climate change is here. This spring, devastating cyclones impacted 3 million people in Mozambique, Malawi and Zimbabwe. Record heatwaves are hitting Europe and other regions—this July was the hottest month in modern record globally. Much of India is again suffering severe drought.

This month’s UN Climate Action Summit was a critical test for leaders to demonstrate a turning point on action. The science says to avoid even worse impacts, we must limit global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius. To achieve this, countries and industries must peak greenhouse gas emissions by 2020 and reduce them to net-zero by 2050.

Meeting these goals is in all our interests. If we don't, climate change could force 100 million people into extreme poverty by 2030. By 2050, we could have 140 million climate migrants. Entire nations are at real risk of disappearing under rising seas.

There is also a clear, positive economic case. A New Climate Economy report found that bold climate action could deliver at least $26 trillion in economic benefits between now and 2030. It could also deliver 65 million new, low-carbon jobs per year in 2030 (equal to the combined workforces of Egypt and the UK today) and lead to 700,000 fewer deaths per year from air pollution.

This opportunity is just as compelling in individual countries. In Indonesia, a government report found recently that a low-carbon development path, more ambitious than the country's current Paris commitment, could deliver GDP growth of at least 6 percent a year until 2045— higher than business-as-usual. This path will reduce poverty more quickly, create more jobs and improve public health. In Mexico, smart actions to reduce emissions could save 25,000 lives and $5 billion over the next 12 years.

Some of the most ambitious action is happening in island nations on the front lines. Last year Jamaica significantly increased its renewable energy target, from 30 percent of its electricity mix by 2030 to 50 percent. Countries like Barbados and Maldives have among the earliest deadlines for carbon neutrality (2030 and 2020 respectively). These countries know there is no time to wait. Their ambition must become the norm.

The International Monetary Fund estimates that the world wastes 6.5 percent of global GDP directly or indirectly subsidising fossil fuels. The health impacts of air pollution, which kill an estimated 4.2 million people each year, make up the bulk of costs. In Africa, air pollution kills more people than childhood malnutrition does, and poses risks on a scale similar to unsafe water or sanitation. Women and children especially are harmed by indoor air pollution from dirty cooking fuels.

Backing out of coal in particular is imperative: emissions over the 30-50 year lifespans of new coal facilities are incompatible with the world reaching net-zero emissions by 2050. However, lack of leadership from developed countries, within their own jurisdictions and in their overseas investments, is slowing action. G7 countries on average produce 19 percent of their electricity from coal. And despite repeated commitments to end fossil fuel subsidies, the G7 still provides at least US$100 billion per year in subsidies to coal, oil and gas.

African countries only account for 2 percent of coal demand, yet are willing and compelled to take a different path. But they need support from partners and financiers. Developed and emerging economies must help deliver the investments for a low-carbon, climate-resilient future.

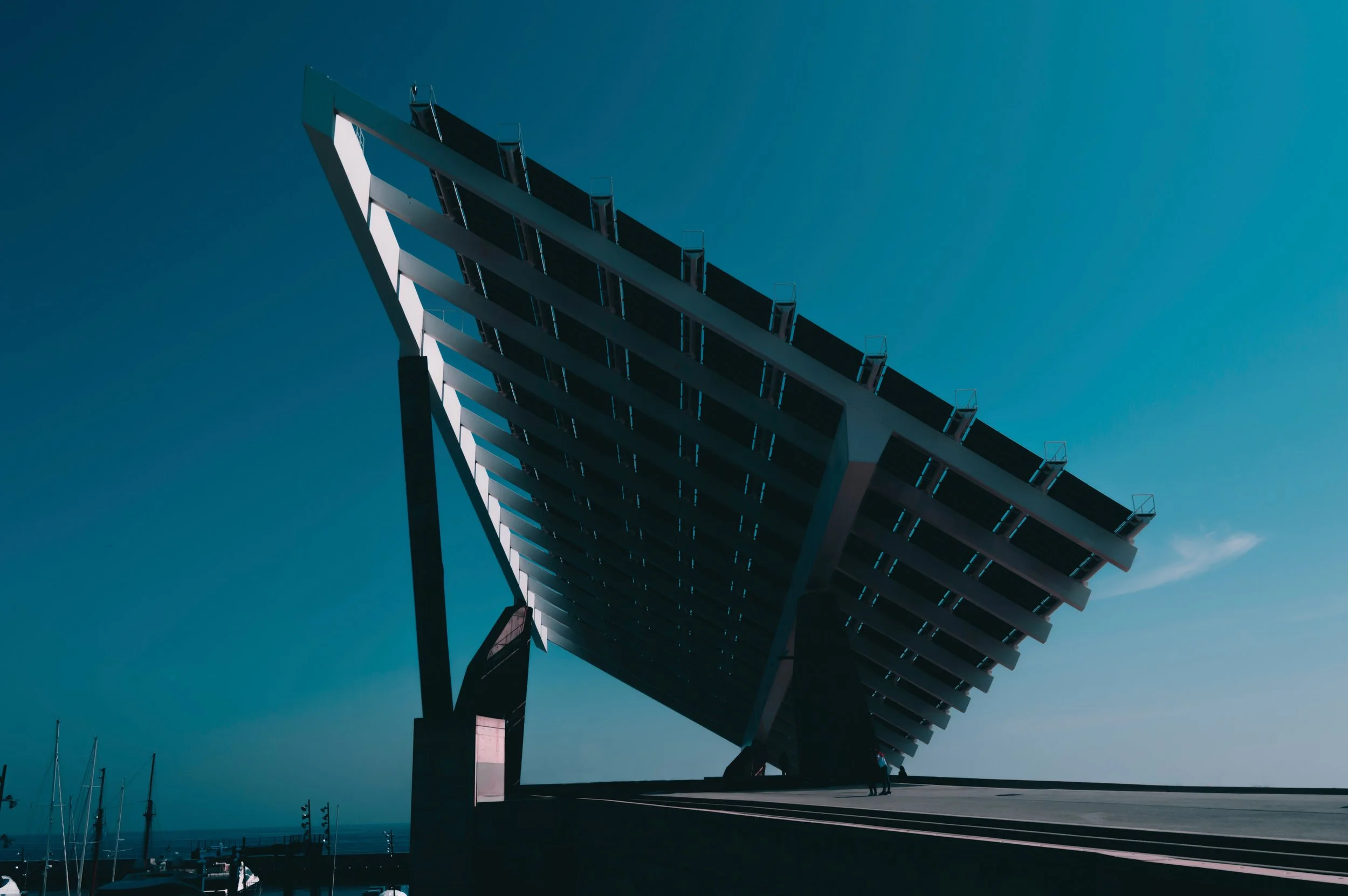

Many regions in Africa are still working to give people electricity. To ensure this electricity is clean, it is time for investors to focus on renewables and stop subsidising coal. Conditions are right: renewable energy prices are dropping, and clean energy is now often the most competitive option. When considering local health costs, coal is more costly than renewables.

African countries are gaining momentum. Morocco recently built the world's largest concentrated solar facility, serving 2 million people. South Africa's robust renewable energy auctions led to solar and wind prices lower than prices from the national utility or from new coal plants. Kenya is the world's 9th largest producer of geothermal power, which generates nearly half its electricity. And across the continent, often the quickest, most affordable and reliable options are a mix of off-grid and on-grid solutions, like household solar panels and solar mini-grids. Companies like Mkopa in East Africa and Lumos in West Africa are providing household and small business solar solutions.

Of course, there are risks and opportunities beyond energy. On land use, the recent IPCC special report didn't pull punches: land is critical both as an emissions source and as a climate solution. This dichotomy is obvious in Africa, where 48 percent of the continent's GDP will be vulnerable to climate extremes in 2023. Meanwhile, research from the Food and Land Use Coalition shows a sustainable approach could produce $320 billion annually in new business opportunities for sub-Saharan Africa.

The climate crisis does not begin or stop with Africa, but African countries can play a leadership role in seizing the opportunities of a better future. The world's larger economies have a responsibility to unlock this future, for themselves and for others. Their voters know this. Children, in the streets calling for action, know this. If the smaller, poorer and vulnerable countries can do it, so can they.