By Jessica Scott-Reid

Jessica is a Canadian writer, animal advocate and plant-based food expert. Her work appears regularly in media across Canada and the US.

In the world of animal and environmental advocacy, documentary films have arguably been one of the most powerful tools. Anecdotally, in conversations with people who have given up consuming meat, for example, documentary films that reveal the carefully hidden side of animal farming are often cited as at least one if not the motivating factor.

Beyond anecdotes, one 2020 study found that “watching a popular documentary about the environmental impact of meat production (Cowspiracy) can have a significant effect on the awareness of the environmental consequences of meat consumption, the attitude toward eating less meat, and the intention to reduce meat consumption of young (almost) daily meat eaters.”

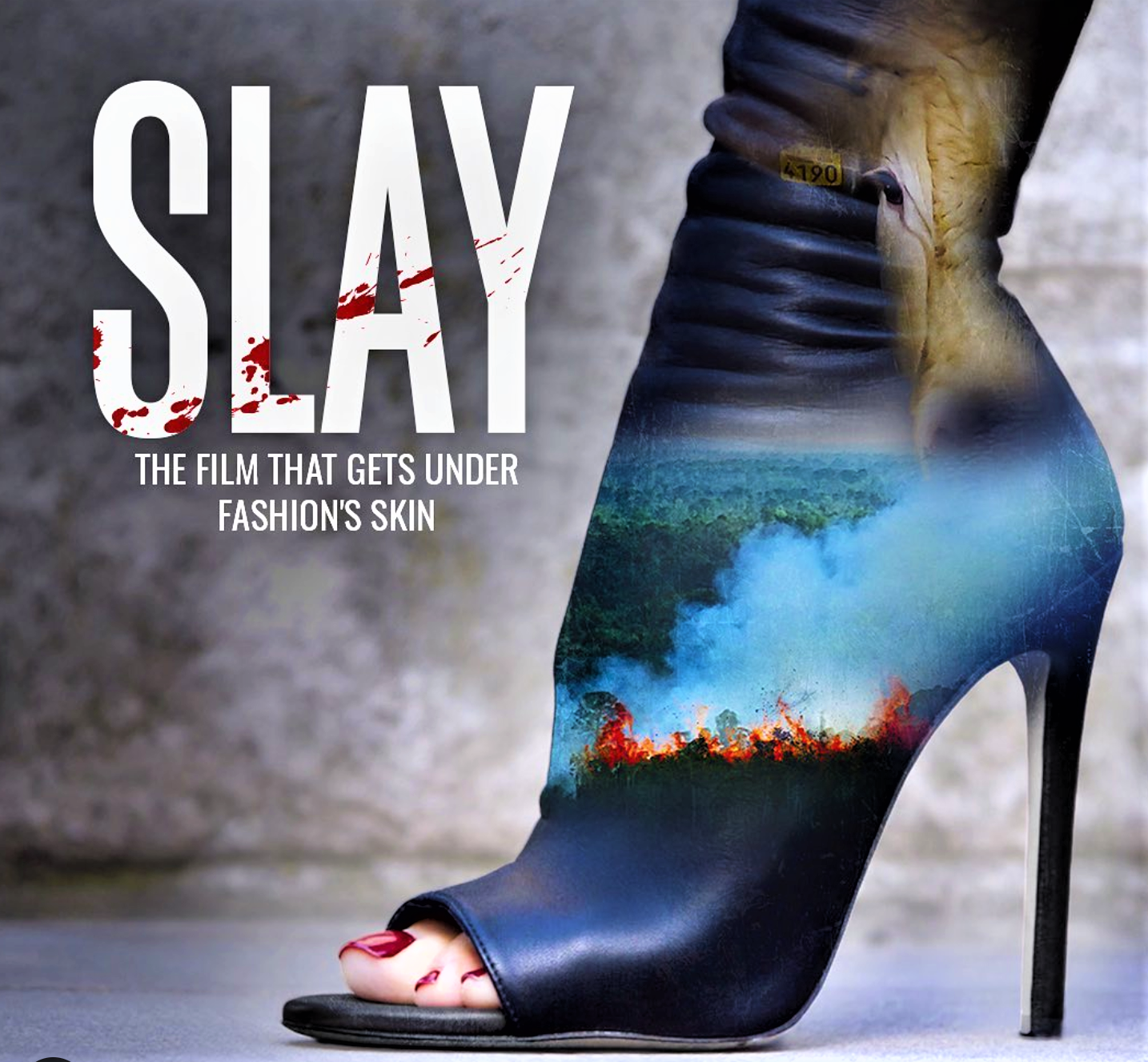

Thus, when filmmaker Rebecca Cappelli, along with producer Keegan Kuhn (Cowspiracy) wanted to explore and expose the use and abuse of animals in the fashion industry, they knew their medium of documentary filmmaking could be very impactful.

And it is. Slay, which focuses on the use of animal skins–leather, fur and wool—in the fashion industry, was shown to a group of over 1000 fashion students and consumers. "Before watching the film, 37 percent of students declared they would not work with animal skins,” says Cappelli in an interview with PFN. “After watching Slay, it is 97 percent.”

“In this system, they are not animals, they are commodities.”

— “Slay” Director, Rebecca Cappelli.

Cappelli believes this survey is a good indication of where the younger generation is headed in terms of fashion and ethics, “when equipped with the right knowledge.” And that right knowledge, showcased in Slay, involves a deep dive into the environmental, economic, animal welfare and human rights issues associated with the use of animal skins in fashion.

Slay is tailored for a mainstream audience, says Cappelli, “someone like me 10 years ago; someone who just enjoys buying and doesn’t ask too many questions.” In a striking moment in the film, Cappelli recalls the point in time when she realized she was “an animal lover wearing animals.”

The film begins with a focus on leather, “because it is the most used animal skin today, by far,” Cappelli says. “We’re talking about 1.5 billion animals skinned for leather. So that’s buffalo, cows, goats, pigs, etc., even dogs,” she explains. And despite many designer leather goods being emblazoned with that sought-after “Made in Italy” or “Made in France” designation, the film shows there is much deception at play. “Most leather is actually produced in the global south,” Cappelli says, “it can come from deforested land in the Amazon, it can come from child labour, it can come from India,” where environmental and human rights concerns (such as tannery worker injuries) are hidden away from the glitzy shops of Europe and North America.

One of the dramatic images in the film shows how producing a single pair of leather shoes requires the same amount of water as one human would drink in 10 years.

Fur fashion is also discussed. Though the fur-free movement is enjoying increasing success—which has seen many top designers turning their backs on fur in recent years—Ed Winters (aka “Earthling Ed”) notes in the film: “what we see is an increasing number of people wearing items such as hats with pompoms or keyrings with pompoms or coats with fur trims. [The fur industry] is aware that people don’t want to buy [fur] anymore and they are undesirable, so they are trying to sneak fur back into the marketplace by making it very subtle.” And while surveys typically show western consumers would not actively choose to wear fur, Slay shows how in some regions, particularly China, the fur industry, from animals farmed and trapped all over the world, is still thriving.

The greenwashing of animal skins versus faux replicas is also touched on in Slay. “One thing that the fur and leather industry has done really effectively in the last several years is take a debate about what happens to animals used for materials, and turned it into a debate about plastic,” says fashion designer Joshua Katcher, in the film. In fact, compared to faux, real fur production emits 7.5 times more GHGs, and only about 25% of a real fur pelt biodegrades, according to research on the fur industry cited in the film.

Slay does not rely on graphic animal cruelty footage for impact although there are some powerful moments, particularly around fur farming and trapping. “I used to have a fur coat,” Cappelli says in the film through tears, while standing outside a row of caged, distressed foxes, “a blue fox coat. I didn’t care. I felt like, 'oh they are already dead so I might as well wear it.' I didn’t understand that because I was buying it that they were living this life. And they were killed for me.”

There are also uplifting scenes in Slay. When showcasing what goes on in the wool industry, Cappelli joins a rescue mission to save baby lambs born alone out in cold, vast fields during an Australian winter. “If I see someone suffering, or someone in trouble, I’ll do what I can to help them,” says a fellow rescuer in the film, “I don’t care what species they are.”

After Cappelli spots a lamb in need, she scoops up the baby and comforts them. With a nudge to Cappelli’s chin, the lamb appears to acknowledge her kindness.

Ultimately, Slay is a film about consumerism and oppression, greed and cruelty, and about erasing the beings who are exploited and killed for fashion. “We call it leather, we don’t call it animal skin,” Cappelli says. “There’s the design, there’s no more smell, the colour is different, the texture is made so that we are disconnected and forget completely about the animals.”

As she echoes in this impactful, thoroughly cited and overall well-made documentary: skins used in fashion help people forget about the animals. “Because in this system, they are not animals, they are commodities.”

The film can be viewed for free at Waterbear, the first interactive screening platform dedicated to the future of our planet. Or it can be rented or purchased on Apple iTunes, Google Play Movies and YouTube.

If you’d like to get involved in some way, visit Take Action on the film’s website.