By Jessica Scott-Reid

Jessica is a Canadian writer, animal advocate and plant-based food expert. Her work appears regularly in media across Canada and the US.

The dairy industry is under threat, from a changing market and changing consumer tastes. As sales numbers for plant-based milk alternatives continue to rise, and Starbucks recently reporting a dominant shift to plant-based products among their consumers, the dairy industry is working hard to remain relevant.

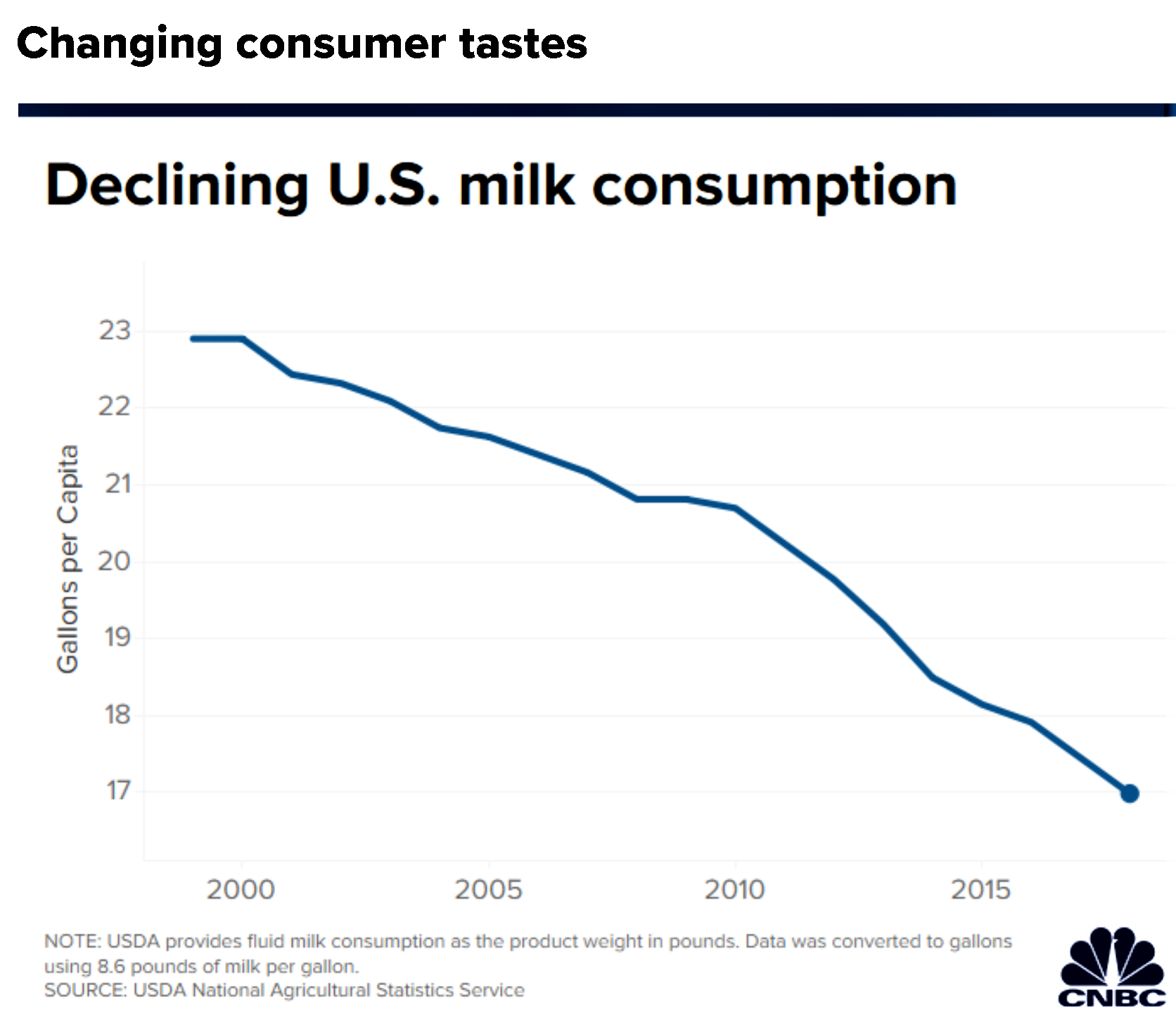

As sales of plant-based milks take off, the traditional dairy market continues to shrink and more dairy farmers leave the business amidst industry consolidation and challenging economics. Despite being protected by supply management systems, the number of dairy farms in Canada in the last decade has shrunk by about half to 5,500. And Canadian milk consumption has declined from 85 litres per capita in 2004 to 65 litres in 2018. US dairy sales have declined even more.

With the help of marketing campaigns, the dairy industries in both Canada and the US are focusing on sustainability to get back into consumers’ hearts. To reach younger generations in particular, the industry has also employed a trendy hashtag, #Februdairy, to promote dairy during the month of February. But as the industry uses these various marketing tools to paint the industry as wholesome, modern and eco-friendly, are consumers getting the real picture?

The dairy industry in Canada bills itself as “a world leader in sustainability.” A 2019/2020 television and online ad campaign entitled “Dairy Farming Forward,” explains how the industry “puts cows first,” how “sustainability is more than just a word, it’s our way of working.”

These are comforting claims for cow milk-consumers who may be concerned about animal welfare and the planet. But, according to Dr. Jason Hannan, an associate professor at the University of Winnipeg, and the author of “Meatsplaining: The Animal Agriculture Industry and the Rhetoric of Denial”, deeming dairy production sustainable and animal-friendly, is problematic.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons CC 4.0.

Environmental researcher Nicholas Carter agrees. Regarding the claim that “the Canadian dairy sector is among the most efficient in the world, with a carbon footprint that is less than half the global average,” he says comparing one country’s harmful industry with another isn’t offering honest context. “The Canadian fossil fuels industry is more efficient than China's coal focused energy, but it really means nothing when there are alternatives with a fraction of the impacts.”

The industry also states that Canadian dairy farming uses just 0.2% of Canada’s total land, and is responsible for only 1% of Canada’s total greenhouse gas emissions. Carter questions how these figures were calculated, which appear to run counter to the methodology used in recent scientific studies on GHG emissions from animal agriculture.

“They definitely used an outdated valuation for methane that lowers it by 2.5x. They also wouldn't have included the value of that land if re-wilded for sequestering carbon from the atmosphere and helping improve biodiversity.”

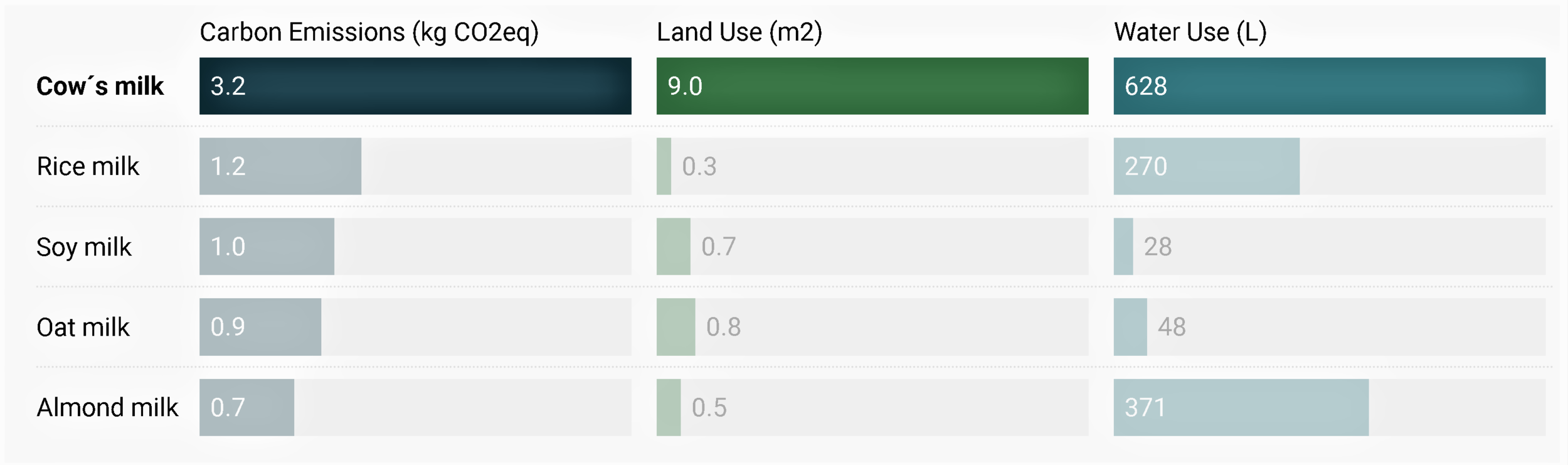

Meanwhile, it is well documented that the production of plant-based dairy alternatives requires far less land and fewer resources, and emits nowhere near the amount of greenhouse gases as dairy production.

A 2018 study done by researchers at the University of Oxford, and published in the journal Science, concluded that the production of one glass of dairy milk resulted in approximately 3x more greenhouse gas emissions than any plant-based milk.

Source: Poore and Nemecek, Science 2018.

"Dairy generally requires nine times more land than any of the plant-based alternatives," writes Dora Marinova, professor of sustainability and Diana Bogueva, postdoctoral researcher at Curtin University in Australia, for The Conversation. "Every litre of cow’s milk uses 8.9 square metres per year, compared to 0.8 for oat, 0.7 for soy, 0.5 for almond and 0.3 for rice milk." The researchers add that water use "is similarly higher for cow’s milk: 628 litres of water for every litre of dairy, compared to 371 for almond, 270 for rice, 48 for oat and 28 for soy milk."

“The dairy industry is very upset about the intrusion of these dairy alternatives into...their market,” says Hannan, pointing to cases of "language policing" (industry attempts to control who gets to use the word “milk” on packaging and in marketing). The industry has been most active challenging labelling in the US and Europe.

The US dairy industry makes similar claims regarding sustainability, doubling down on growing consumer concerns regarding the industry’s treatment of animals and the planet by portraying dairy farmers in the US as “caretakers of animals and the land.”

Plant-based milks have a much lower environmental impact than dairy milk.

Source: Univ of California, Davis

In addition, claims about increased efficiency in dairy production, as a method for sustainability, often gloss over the fact that this typically means increased intensification (more and bigger factory farms), and a subsequent higher cost to animal welfare.

Omitting certain aspects of animal welfare is common in dairy marketing. One example is a recently created online marketing course for high school students in Ontario. In the module called “How Cows Make Milk”, major components in the milk production process are omitted. Students never learn how dairy cows must be continually impregnated and giving birth, or how their calves are taken away soon after birth, all in order for their milk to be rerouted for human consumption.

This marketing method, says Hannan, is a direct response to a growing campaign by animal activists “to expose the dairy industry because of the horrific treatment of animals.”

And part of that campaign has been to take over the #Februdairy hashtag, now used by animal and environmental activists, and plant-based food advocates, to counter dairy marketing with many of the hidden truths of the dairy industry, and to promote the benefits of the many plant-based alternatives now widely available.

Another notable challenge this month came from Oatley which aired a commercial during the US Super Bowl promoting its oat milk as “like milk but made for humans”.

As their jingle says, “Wow, wow, no cow”!