By Liz Kimbrough

This story originally appeared in Mongabay and is published here as part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalistic collaboration strengthening coverage of the climate story.

In a first-of-its-kind effort, scientists have calculated the balance of all natural and human-caused greenhouse gases coming in and out of the Amazon Basin — and found that the region is now a net emitter.

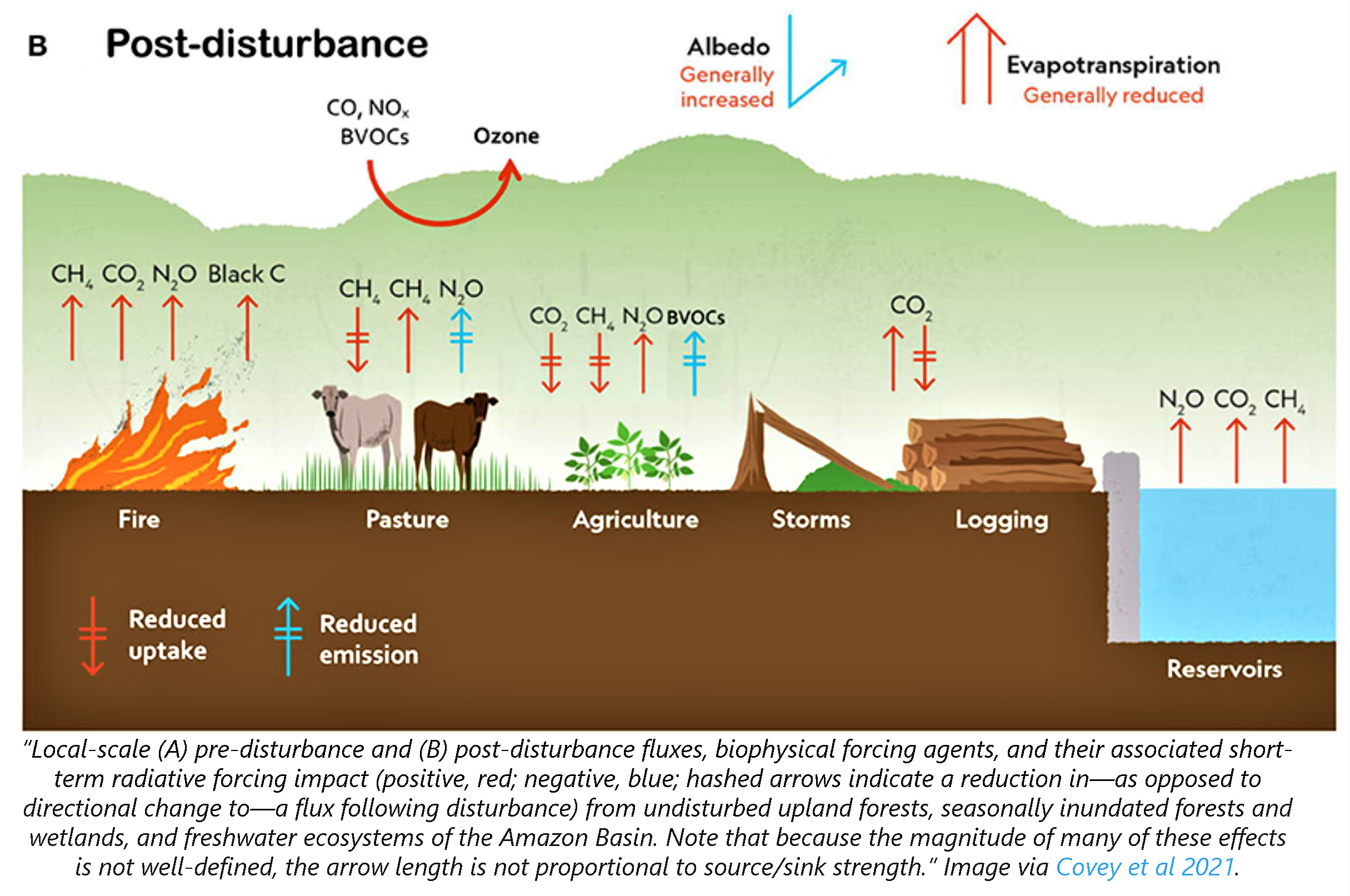

In a new study, the scientists say human disturbances, and not natural greenhouse gas emissions, are contributing to climate change.

Carbon dioxide isn’t the only problem; fires and drying out of seasonally flooded forests release large volumes of methane and nitrous oxide, which are even more potent greenhouse gases than CO2.

The finding suggests forests alone won’t be enough to slow climate change as long as we continue burning fossil fuels.

Something is wrong in the lungs of the world. Decades of burning, logging, mining and development have tipped the scales, and now the Amazon Basin may be emitting more greenhouse gases than it absorbs.

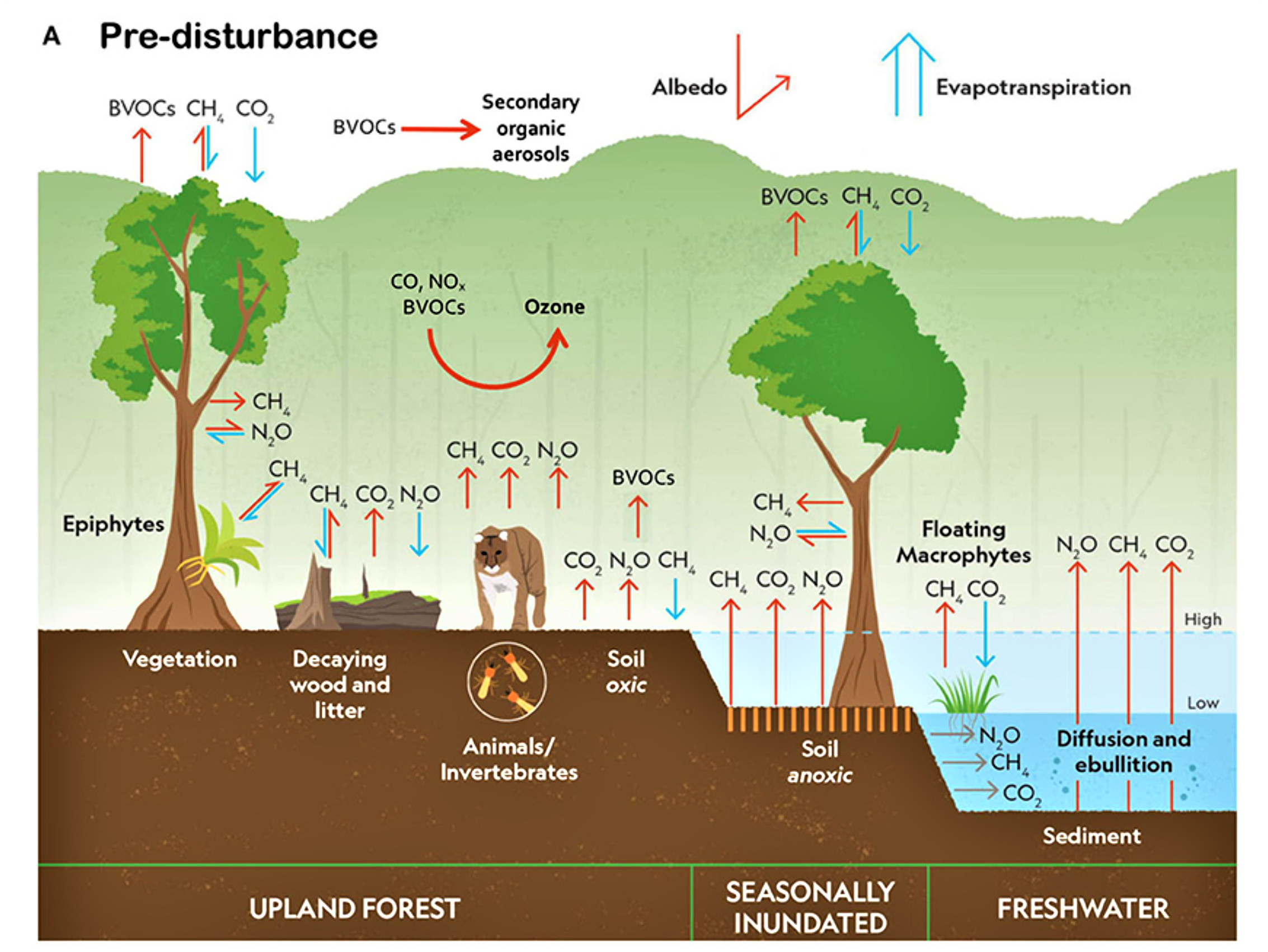

Most of the conversation about climate change is dominated by carbon dioxide. While CO2 plays a critical role in the complex climate equation, other forces such as methane, nitrous oxide, aerosols and black carbon are also factors.

In a first-of-its-kind effort, a group of 31 scientists calculated the balance of all natural and human-caused greenhouse gases coming in and out of the massive Amazon Basin. The team concluded that warming of the atmosphere from agents other than CO2 likely exceeds the climate benefits the Amazon provides via CO2 uptake. Or more simply: due to humans, the Amazon Basin is now a net greenhouse gas (GHG) emitter.

“I would highlight that natural greenhouse emissions from ecosystems aren’t causing climate change,” the study’s lead author, Kristofer Covey, an assistant professor at Skidmore College told Mongabay. “It’s the many human disturbances underway in the basin that are contributing to climate change.”

Photo: Rainforest Partnership

Earth receives constant energy from the sun. Climate-forcing factors in the atmosphere, such as greenhouse gases, act like a blanket, trapping that heat energy on Earth. When there’s more energy coming in from the sun than is being reflected back out into space, the planet warms and our climate is thrown out of balance.

A healthy forest ecosystem sucks in CO2 and keeps other climate-forcing factors in relative balance. But in the Amazon, where forests have faced increased logging, mining, dam construction, and clearing for agricultural (typically using fire), the system is drying and degrading. One study found that the amount of aboveground plant tissue in the Amazon was reduced by roughly one-third over the past decade.

In short, the ability of the Amazon to absorb CO2 is declining.

At the same time, other climate-forcing factors are on the rise. When trees burn, for instance, they not only release their stored CO2, but also release methane — a GHG more than 80 times as potent as carbon, which sticks around in the atmosphere for much longer, amplifying the warming.

Photo: NASA via Wikimedia Commons

Warming, especially of the soils and sediments in the Amazon’s seasonally flooded forests, contributes to increased emissions of methane and nitrous oxide—a GHG with 300 times the warming potential of CO2. “Of the impacts that may increase the strength of sources in the Basin, wetland warming and reservoir construction [dams] could be the most significant,” the paper says.

Black carbon, small particulate matter from fires and the incomplete combustion of fossil fuels, settles and darkens the surface of the Earth, causing it to absorb more heat. Soot from Amazon fires has been found in the Andean glaciers, reducing the albedo, or reflectiveness of snow, thereby increasing melting and altering hydrology.

“Parsing the complex interactions between the Amazon, its effects on climate, and human influences is a bit like trying to predict the stock market,” said study co-author Fiona Soper, an ecologist at McGill University in Canada. “[I]t’s made up of moving parts: multiple climate forcers, not just carbon but also methane, nitrous oxide, particulates and biophysical effects, each being acted on by human stressors that range from dam building and hunting to climate change…Synthesizing these changes is a huge challenge.”

Evapotranspiration, the natural exchange of gases and water from plants into the atmosphere; aerosols, small particles produced both naturally and by burning; ozone, a trace gas usually produced from urban emissions and fires; and biogenic volatile organic compounds, trace gasses produced by plants, are all accounted for in the study.

However, despite their best estimates, researchers note some uncertainty in the magnitude of emissions from the Amazon Basin, disagreements about the best way to compare the climate forcing of non-CO2 factors relative to CO2, and the exact roles of these climate-forcing factors.

“I think this paper does a great service by highlighting how much there is to learn about the biogeochemistry of the Amazon Basin, particularly about non-CO2 greenhouse gases and other forcing factors on climate,” Ruth DeFries, a professor of sustainable development at Columbia University who was not involved in the study, told Mongabay.

“Forests might not be able to sequester enough carbon to provide a net benefit for climate mitigation, which suggests that efforts to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases depend on alternatives to fossil fuel burning — the largest and well-quantified source of anthropogenic greenhouse gases.”

Many climate experts agree that reducing emissions is an essential focus to address climate change. But this doesn’t mean the services of the Amazon Basin are a wash. The remaining forests are still doing a mammoth job of stabilizing the climate, not to mention supporting rich biodiversity, cultures and livelihoods.

“The main take away from this work,” Soper said, “should be a call to arms to prevent further degradation of the Amazon system.”