By Jessica Scott-Reid

Jessica is a Canadian writer, animal advocate and plant-based food expert. Her work appears regularly in media across Canada and the US.

Many of us may be sick of hearing and talking about pandemic risks, about zoonotic diseases and what the future could hold in the face of still-emerging viral infections. (If only being sick of it made it go away.) But according to a recent report from the Center for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC), there is a current global outbreak that is ramping up and demanding our continued attention: avian influenza, or “bird flu.”

Although human cases of bird flu remain relatively rare for now (less than a thousand cases documented in the last 20 years), the virus is reportedly spreading beyond farmed and wild bird flocks to farmed fur-bearing animals, and even to domestic cats, with reports of the number of cases of transmission to humans also increasing. And, more than half of the cases in humans have proven fatal according to the World Health Organization (WHO). The only way to put a stop to it, according to some experts, is to rethink factory farming.

Photo: Shagra Kopstein on Unsplash

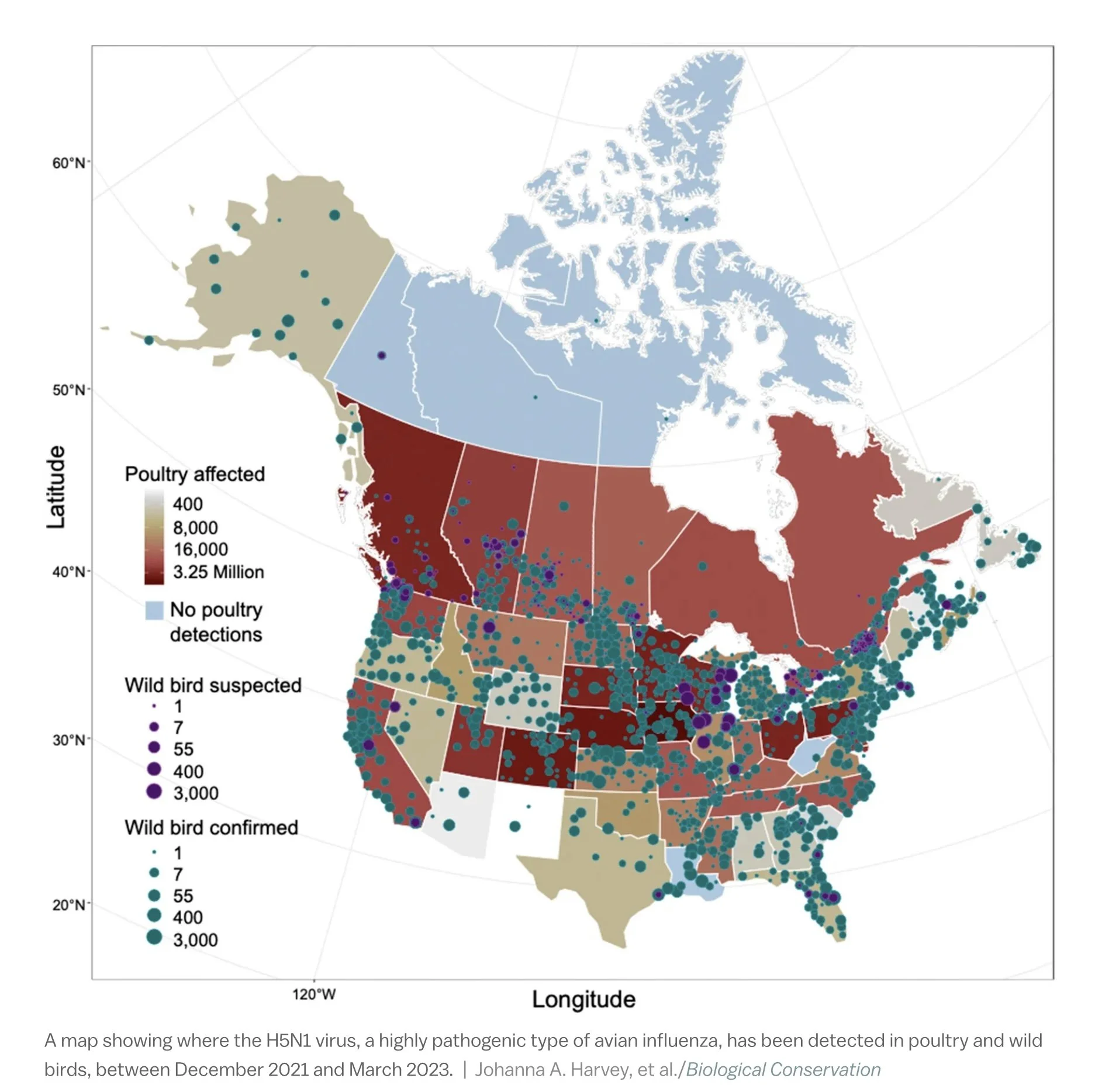

According to the CDC, the “number of reported avian influenza (AI) ‘bird flu’ outbreaks in animals and infections in people are increasing worldwide.” This further geographical spread, it continues, “could be attributed to increased poultry production and commercial trade, increased exposure to wild birds through repeated annual migrations of infected birds, and changes in migration patterns because of climate change or land conversion to agricultural production.”

Seven and 17 day-old broiler chickens are bred to grow at unnaturally rapid rates and are slaughtered at five to six weeks of age. This shed contained tens of thousands of birds. Photo: Jo-Anne McArthur, Animal Equality / We Animals Media

But a recent report from animal and environmental advocacy group Compassion in World Farming (CIWF), claims wild birds are not responsible for the spread. “Contrary to popular belief, wild birds are typically victims of the disease rather than the cause,” adding that bird flu is spiralling out of control due to the rise of factory farming. “This view is supported by the international Scientific Task Force on Avian Influenza, which was set up to provide governments with recommendations and guidance,” it says.

Huge numbers of a wide range of wild birds including eagles, ducks, geese and these Northern Gannets have died from bird flu. While wild birds can spread avian flu, they are more often the victims, infected by avian flu from large scale poultry operations. Photo: Stella Noakes, iNaturalist, CC-BY-NC 4.0

CIWF further asserts that “without major reforms to industrial farming it will not be possible to end the spread of bird flu or reduce the risk of a global human pandemic.”

Factory farms, where animals are raised for either food or textiles (fur, leather, wool, etc.) act as potential petri dishes for disease. When animals are housed together in great numbers, overcrowded in unhygienic conditions, diseases can flourish. “Factory farms create the ideal conditions for the spread of the disease as they give viruses a constant supply of hosts – allowing infections to spread rapidly – and for highly harmful new strains to emerge,” says CIWF.

Factory farms that cram thousands of animals together in unhygienic conditions, such as this aerial view of the largest fur farm in Finland, are at high risk from pathogens like bird flu and contribute to the spread of the disease. Photo: Oikeutta eläimille / We Animals Media

Since 2021, over half a billion farmed birds have died or have been killed globally due to bird flu.

When highly infectious diseases are detected on factory farms, the go-to method to attempt to stop the spread is typically mass, on-farming killings, also known as culling. A common method for on-farm culling in North America is ventilation shutdown, which involves closing and shutting down airflow into a barn while heat is increased. The animals trapped inside suffocate and/or die from heatstroke.

Another method is ventilation shutdown-plus, which includes piping in CO2 gas. Various animal advocacy groups have called for an end to this inhumane practice. For example, Veterinarians Against Ventilation Shutdown is demanding that the American Veterinary Medicine Association (AVMA) reclassify all forms of ventilation shutdown as “Not recommended” methods of mass animal killing.

A tractor carries a load of dead turkeys infected with H5N1 out from the shed where they were killed during a disposal operation at a farm with an avian influenza outbreak. Wymondham, Norfolk, United Kingdom, 2022. Photo: Ed Shephard, Generation Vegan, We Animals Media

CIWF’s chief policy adviser and the report’s author, Peter Stevenson, calls bird flu “a ticking time bomb.” He says that “unless we wake up and take urgent action to end factory farming we will simply be unable to stop its rapid spread across the globe or reduce the risk of a serious human pandemic developing.”

But while that urgent action laid out by CIWF includes a three-point plan—vaccinating flocks, reducing flock sizes and revamping the ways in which animals are farmed—other experts say we need to take it further. Dr. Michael Greger author of “Bird Flu: A Virus of Our Own Hatching”, says “If you actually want to create global pandemics, then build factory farms.” Also, since the COVID-19 pandemic, increasing demand for animal proteins has been identified by the United Nations Environment Programme as a key contributor to pandemic risk.

Photo: Alex Teixeira on Unsplash

As a result, calls for food system change have grown louder, including funneling more support for plant-protein and cell-based meat production. As one Canadian member of parliament, Ontario Liberal leadership candidate Nathaniel Erskin-Smith told PFN in 2022: Encouraging the government to promote lower-risk alternatives is not only important, but also likely more useful, as supporting one industry will always be easier than regulating another.

Lobbying local leaders who have the power to push for these types of policy and systemic changes, is just one way everyday citizens can help lower the public health risks associated with bird flu and other zoonotic diseases. Subsidies for alternative proteins production, which do not require the farming of animals, are currently a tiny fraction of the subsidies used to support industrial animal agriculture so we can overeat cheap meat.

A recent analysis from Stanford University found that from 2014-2020, the US livestock sector received about 800x more public funding than meat, egg, and dairy alternatives. Other powerful steps we can take include withdrawing our support from factory farming by eating less meat and dairy along with discussing the importance of these choices with family, friends and community members.

Plant-based burger

So, sure, we may be sick of thinking about pandemics, but as The New York Times columnist Zeynep Tufekci writes: “since the coronavirus pandemic taught us the importance of responding early and aggressively to outbreaks … Sorry, I’m joking. We don’t seem to have learned much from the Covid outbreak, and it’s not funny.” Not only must we continue thinking about possible pandemics, but acting fast to prevent them remains more crucial than ever to avoid walking blindly into another, and possibly more deadly, one.