Music has been at the forefront of social change for generations — protesting war, racism and inequality — capturing hearts and minds and inspiring action. But today there is a curious dearth of protest songs about the existential challenge of our time, the destruction of the environment and the climate crisis. Now the Australian music community is seeking to change that.

Launched during the UN COP26 Climate Summit last November, the Environmental Music Prize (EMP) is a $20,000 prize that amplifies the voices of artists who inspire action for climate and conservation.

The prize, which has attracted more than 200 entries from Australia’s leading musicians, was created by Australian Edwina Floch, when she realized there was no notable climate anthem. More on the prize in a moment.

So, why are there no recognizable environmental protest songs? Part of the answer lies in how and where we listen to music today.

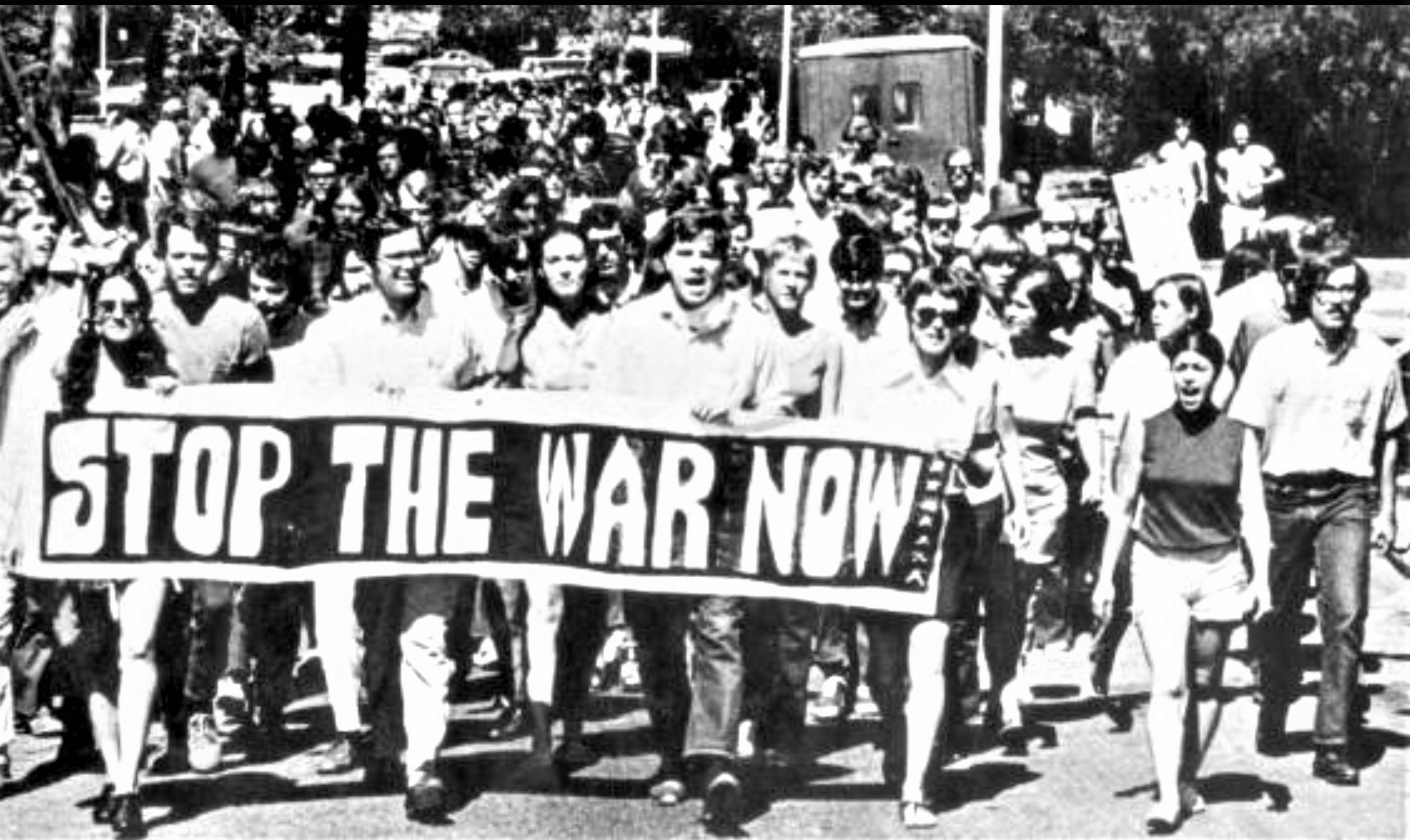

The 1960s and early ‘70s were the heyday of protest music when people listened to Top 40 radio, TV shows like Soul Train and attended music festivals like Woodstock. Because people were listening to the same music, there was a common soundtrack to life. Protest songs were a shared experience, part of the zeitgeist of young people, a driver of social change, a form of political protest and a source of common anthems.

Photo: Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young (CSN&Y). Photo: CC-BY-SA 4.0 Wikimedia Commons

The soundtrack focused on the issues of the day — war, racism, and inequality. It ranged from We Shall Overcome sung by Joan Baez and Blowin’ in the Wind by Bob Dylan to CSN&Y’s (Four Dead in) Ohio. It was the anti-war I Think I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag by Country Joe and the Fish, made famous at Woodstock, and War by Edwin Starr. And the haunting sounds of Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On. The civil rights campaigns of the 1960s embraced the gospel tradition, songs like Amazing Grace, the music of Aretha Franklin and Sam Cooke’s anthemic A Change Is Gonna Come.

Big Yellow Taxi by Joni Mitchell, Mercy, Mercy Me by Marvin Gaye, and Helen Reddy’s I am Woman, were tracks about the environment and women’s rights. The protest song catalogue was deep and wide and iconic songs became part of the change — adopted by and sung at protests, marches and demonstrations.

Artists have long used their celebrity status to raise awareness and press for action. Benefit concerts and group videos have raised money for famine relief, world hunger and AIDS — all starting with George Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh in 1971, for victims of the war between Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Today, that common soundtrack is missing because of how we listen to music. With streaming, self-curated playlists, and social media, music has become an individualized experience — customized and splintered — with little common ground and few shared theme songs.

So even though there are protest songs today, their impact is fragmented and therefore diminished. Rap and hip-hop artists like Kendrick Lamar sing about racism and inequality, and there is still the more traditional approach with The Ballad of George Floyd. There are protest songs about the war in Ukraine including: Kiev Calling by Ukrainian punk band Beton (a remake of London Calling by The Clash); Hey Hey Rise Up, a new song by Pink Floyd who perform it with Ukrainian rock star-turned-soldier Andriy Khlyvnyuk; and the widespread support for Ukraine’s Eurovision Song Contest winner Stefania by Kalush Orchestra.

And while some musicians, ranging from Moby to Billie Eilish, are speaking out about climate, environmental and animal issues, there are very few protest songs on these topics.

Australia’s EMP is a global first that is designed to change that. It is a call-to-action for musicians to create powerful music videos that celebrate nature and encourage us to defend our planet. Rather than being merely another music award, the prize focuses on impact, with a goal to educate and empower artists to use their voices and influence to become climate leaders.

Australian musicians have been leading the way for some time. Back in 1987, Midnight Oil, a band with a track record of supporting progressive causes, released their prophetic song (How Can We Sleep When Our) Beds Are Burning. This year they released an entire album, Resist, about the climate crisis focused on inspiring people to take action.

The 24 EMP finalists in the competition ranged from indie pop artists Lime Cordiale to the aboriginal rock band King Stingray. And people were able to vote for their favourite. We Are The Youth, a track by Australian musician Jack River, is dedicated to the youth climate strikers who are leading the vanguard on climate action.

“This song is for the kids staying up late to organize a protest, for the billions of young people driving urgent political and social change. The actions of this generation will define the destiny of humanity and the planet for the rest of time.”

— Jack River

Another finalist, Sydney-based hip hop artist L-Fresh The Lion, says he wrote his song Mother out of his frustration and impatience with how we take this planet for granted.

“Conversations on climate change continue just as conversations, while the climate is changing — fires, floods, new norms being defined … I’m over the conversation.”

— L Fresh The Lion

“In Mother, I say … We need solutions. And we need action. You wouldn’t be just talking if you saw your mother suffering in front of your eyes. You’d do something to help her out. Our planet gives us life. And it’s suffering,” says L-Fresh The Lion.

Check out all the finalist videos here.

And the winner of the first Environmental Music Prize (announced in mid-June) was the Australian band King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard with their climate anthem and accompanying video, If Not Now, Then When?

The band, who won more than 7,500 votes submitted from 58 countries, has donated all the money from the prize to The Wilderness Society that focuses on conservation in Australia.

"It’s fantastic and deeply important for initiatives like this one, to help build community around the fight against the climate crisis," said front man Stu Mackenzie.

In 2023, the Environmental Music Prize will be a global contest, seeking to spread the call to climate action around the world. And maybe, once again, music can play a role in mobilizing people to embrace change.